Once the primary recording studio of Chess Records, Willie Dixon’s Blues Heaven is a shrine to some of the best and most legendary music ever laid to wax.

“It’s on every one of my tours,” says Wayne Galasek, a guide with Al Capone’s Chicago. A smile spreads across his face, causing his finely waxed handlebar mustache to curl even further as he leads his current tour group into 2120 S. Michigan Ave. “Folks,” he tells them, “you’re about to enter the Garden of Eden of rock ‘n’ roll.” Blues, jazz, gospel, and soul would be more accurate, but each genre’s connection with rock is undeniable, and the crowd still buzzes with excitement. After all, a dream team of music legends has recorded at 2120, which once served as the headquarters of Chess Records. At the height of its fame in the 1950s and ‘60s, the Chess roster read like a who’s who of blues and R&B: Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker, Aretha Franklin, Muddy Waters, Etta James—the list goes on. Photos of many of these greats line the shoebox-size lobby, where we’re greeted by Willie Dixon’s jovial yet soft-spoken grandson Keith. Although his late grandfather is recognized as having been a pioneer of Chicago blues and a prominent vocalist, bassist, songwriter, and producer at Chess, Keith remembers him differently. “I just saw him as the old guy who’d get up at 6 a.m. to make me oatmeal,” he laughs.

We’ve stepped from the lobby to the second story, home to Chess’s spacious former recording room. Keith, after amusing his audience with more stories about Willie, a one-time boxer who taught his grandchildren how to sneak in jabs during games of patty-cake (“I punched Chuck Berry, I punched Bo Diddley”), points out some of the odd architectural features left over from Chess’s heyday. For one, you won’t find parallel walls in many of the rooms. The different angles made for different sonic atmospheres, with one wall made up of nine panels that could be adjusted at will. Open panels meant greater sound reduction.

But Chess is most famous among audiophiles for its homemade echo chamber. When recording, musicians would sing into a microphone that was wired to an amplifier in the basement. Their voices poured from the speaker and into the cavernous space, where another microphone picked up the sound and sent it back to the control room upstairs, which was separated from the recording room by a pane of soundproof glass. The setup is responsible for the lonely yet somehow full effect heard on many of Chess’s most famous recordings (see Muddy Waters’s “Hoochie Coochie Man”).

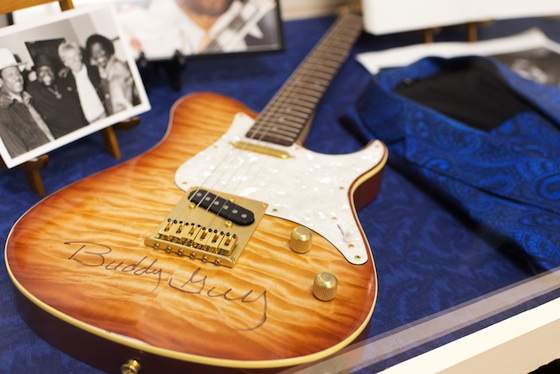

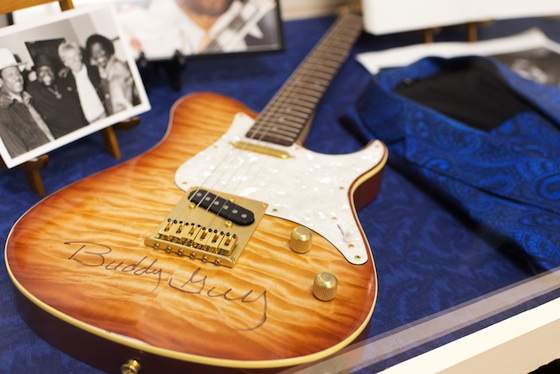

Today, most of the recording equipment is gone from the control room and basement, but visitors can see some of it placed throughout other sections of Blues Heaven. Aged amplifiers and consoles sit among the memorabilia, nestled between glass cases filled with Grammy Awards, gold records, and cream- and copper-toned guitars once played by Buddy Guy. Downstairs, a rear room formerly used for pressing and shipping out records further showcases the building’s rich history, especially on the south wall. Its surface is covered with plaster face casts of many Delta bluesmen, each one created by blind sculptor Sharon McConnell-Dickerson.

Despite its trove of musical artifacts, Blues Heaven is more than just a museum. When Willie Dixon’s widow, Marie, purchased the property in 1993, she wanted to continue her husband’s philanthropy, from assisting Chicago college students with their educations to helping blues musicians reclaim the rights to their songs. These goals have been fully realized through the Blues Heaven Foundation, whose programs include the Muddy Waters Scholarship and the Royalty Recovery & Legal Assistance Workshop.

As Galasek leads his tour group back out into the brisk Chicago winter, a tinny voice reverberates throughout 2120, warbling underneath a crackle of guitar. It gets louder as I head toward the exit, and I expect to see Willie Dixon himself hunched over on a stool, singing his heart out. As I round the corner that leads to the gift shop, I discover that it’s just a radio playing one of Dixon’s records. Keith stands behind the counter, smiling. Chess might not be putting out any more albums, but the spirit of the blues is alive and well in the Windy City.