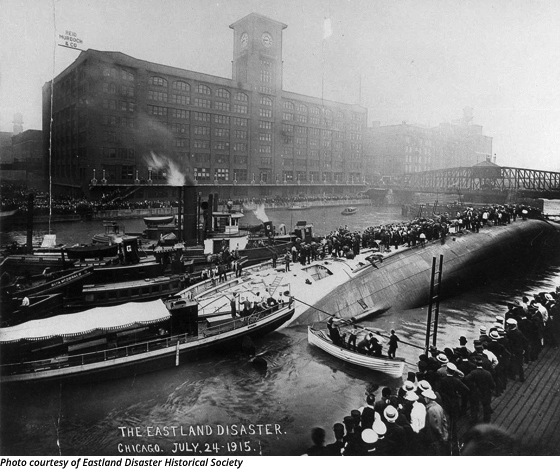

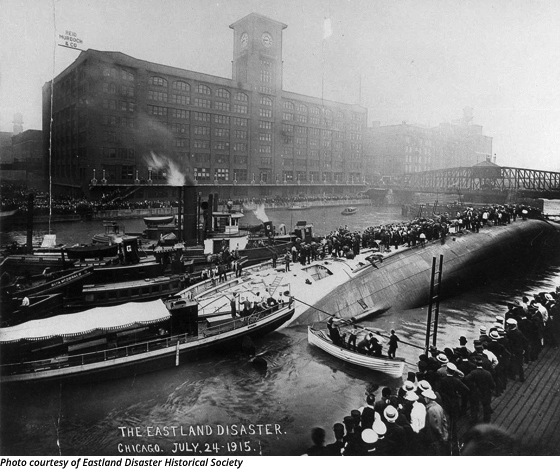

On a small stretch of the Chicago River between Clark and LaSalle Streets, 844 people perished in a matter of minutes. They were passengers aboard the SS

Eastland, a steamer that sank en route to Indiana for a company picnic on July 24, 1915. Though the disaster made

headlines in its day, most Chicagoans today pay no mind to the waters just opposite the Reid Murdoch Center. But as 2015—the centennial anniversary—approaches, a few local historians are trying to change that.

“There’s easily several million people alive today who have direct family connections to the tragedy itself,” says Ted Wachholz, the executive director of the

Eastland Disaster Historical Society. Despite growing up in Illinois, Wachholz didn’t know about the event until he was 25 years old. That’s when he met his wife, whose grandmother, Borghild “Bobbie” Aanstad, was a survivor.

What Aanstad witnessed is specific to

her own story of survival. The more general account of the accident is no less harrowing. The

Eastland was still tied to the wharf, just several feet from the shore, when it rolled onto its port side. Its passengers were employees of a single company or family members of those employees. Many of the victims were trapped below deck, while others simply couldn’t swim. Witnesses jumped into the water to help save passengers, and boats lined up to rescue those who had been able to climb aboard the ship’s side.

Though experts disagree on the precise cause, most acknowledge that it was probably a combination of honest mistakes and Murphy’s Law. The ship was unstable by its initial design, and modifications made over its 12 years of service only added to this instability. A major piece of the puzzle was the

Titanic’s ironic contribution: the crew had added lifeboats to the top decks to comply with new laws, despite the fact that the ship was not designed to hold them. Additionally, the water system in the ballasts—whose purpose is to keep an even keel—was not performing properly, so the tanks were only partially full. This lack of balance was especially problematic since the ship was boarded by a whopping 2,500 people.

It’s this very issue of the ship’s capacity that led to one of the biggest rumors surrounding the

Eastland disaster: that crowds rushing the deck’s port side caused the boat to tip. “Based on court transcripts, every person that testified under oath said there was no sudden movement of the passengers—which is contrary to popular belief—because the deck was too crowded,” Wachholz says.

In the end, nearly one-third of those passengers lost their lives, spurring the city to open temporary morgues at both the Reid Murdoch Center and the Second Regiment Armory, a building that today houses Harpo Studios.

You can pay tribute by visiting the site or finding out more via a number of tours and exhibits.

By Foot

It’s easy to miss, but a lone

plaque dedicated by the city of Chicago and the

Eastland Disaster Historical Society has stood on Upper Wacker Drive since June 4, 1989. If you venture across the bridges to the Reid Murdoch Center, you can peruse a photo essay titled “A Day Unlike Any Other” in the lobby and gaze across the river to the very spot of the capsizing.

By Kayak

James Morro first learned of the disaster in the same way his customers do: while sitting atop the waters that filled half of the doomed ship. “My ears kind of perked up when [the guide] started telling that story,” he says. “It’s a shocker.” Soon thereafter he and that guide, his buddy Aaron Gershenzon, founded

Urban Kayaks. Together they continue to share the story with customers on their Historic Chicago and Sunset Paddle tours, but not without a couple of light touches. “We like to scare everyone once in a while,” he says. “We tell people that every time we tell this story, someone falls in,” and at that point a member of the staff might rattle a kayak or two. “We get a couple of good screams.”

By Ghost Tour

Ursula Bielski grew up in a haunted house on Chicago’s North Side. That, combined with the tales of Chicago history that her father—a police officer—used to tell her, inspired her to study a different dimension of the city’s past: that of the paranormal. Today, she has published several books and amassed a dedicated fan base, though educating more people about the

Eastland’s history is a personal mission. The site has served as one of the fundamental stops on her

Chicago Hauntings tours since she started the business 10 years ago. “Thousands of people come up to me at the end of our tours and say they never knew what happened,” Bielski says. “By doing this we’re helping to lay to rest the turmoil. … The more haunted places are those that people don’t talk about.”

By Museum Visit

About 2 miles north of the disaster site, artifacts from the ship are on display in the

Chicago History Museum’s permanent exhibit,

Chicago: Crossroads of America. In a section titled “City in Crisis”—among displays depicting Chicago’s gangland and the Great Chicago Fire—the

Eastland disaster “gets a nice piece of real estate,” says Libby Mahoney, the museum’s chief curator. Objects such as the ship’s brass steering wheel and whistle, a folding chair, a stateroom key, and baggage tags are assembled along with a diagram illustrating the ship’s instability that was published in the

Chicago Tribune the day after the disaster. Perhaps most poignant are the photographs of the rescue efforts taken by photojournalist Jun Fujita, some of which are on display and some of which are accessible through the museum’s research center. “It’s such a grim, grim story,” Mahoney says. “The city rebuilt itself after the fire, but you can’t rebuild all those families that lost their lives.”

On a small stretch of the Chicago River between Clark and LaSalle Streets, 844 people perished in a matter of minutes. They were passengers aboard the SS Eastland, a steamer that sank en route to Indiana for a company picnic on July 24, 1915. Though the disaster made

On a small stretch of the Chicago River between Clark and LaSalle Streets, 844 people perished in a matter of minutes. They were passengers aboard the SS Eastland, a steamer that sank en route to Indiana for a company picnic on July 24, 1915. Though the disaster made