GROUPON GUIDE TO CHICAGO

How Kwagala Project Fights Human Trafficking, One Necklace at a Time

BY: Halley Lawrence |Jan 7, 2014

Even after Joyce escaped from a militant group of kidnappers, she was sleeping in the streets of a Ugandan ghetto. Then she discovered this design nonprofit.

One afternoon in 2005, a 14-year-old Ugandan girl named Joyce found herself staring into the barrel of a machine gun. It happened quickly—she’d just stepped away from her family’s hut to fetch kindling from a woodpile. She could still see her home from where she stood, but with an automatic weapon in her face, she had no choice but to follow the orders of the person pointing it at her.

That person was a member of the Lord’s Resistance Army, a militant group whose numbers are said to be continuously replenished by kidnapped children. Joyce spent the next two years in an LRA encampment, where rape, murder, mutilation, and forced prostitution were regular occurrences.

But then one night in 2007, gunfire ripped through the camp. In the frenzy, Joyce grabbed her shoes and ran into the darkness. It took her days to get back to her own village; upon returning, she discovered her family had been killed and she had nowhere to live. She set off for nearby Gulu, where she starved and slept in the streets. When she was discovered by a group of teenage girls, they brought her back to their ghetto and introduced her to their only means of survival—selling their bodies.

Even after Joyce escaped from a militant group of kidnappers, she was sleeping in the streets of a Ugandan ghetto. Then she discovered this design nonprofit.

One afternoon in 2005, a 14-year-old Ugandan girl named Joyce found herself staring into the barrel of a machine gun. It happened quickly—she’d just stepped away from her family’s hut to fetch kindling from a woodpile. She could still see her home from where she stood, but with an automatic weapon in her face, she had no choice but to follow the orders of the person pointing it at her.

That person was a member of the Lord’s Resistance Army, a militant group whose numbers are said to be continuously replenished by kidnapped children. Joyce spent the next two years in an LRA encampment, where rape, murder, mutilation, and forced prostitution were regular occurrences.

But then one night in 2007, gunfire ripped through the camp. In the frenzy, Joyce grabbed her shoes and ran into the darkness. It took her days to get back to her own village; upon returning, she discovered her family had been killed and she had nowhere to live. She set off for nearby Gulu, where she starved and slept in the streets. When she was discovered by a group of teenage girls, they brought her back to their ghetto and introduced her to their only means of survival—selling their bodies.

A Glimmer of Hope, Halfway Around the World

Nearly 8,000 miles away in Chicago, Kristen Hendricks was spending her free time ladeling out meals at local soup kitchens. Her day job was operating a private-label handbag and accessories company. But when she started learning about human trafficking in Africa, her life’s passion changed. She spent months researching it, then booked a trip to Uganda to see its reality firsthand.

“It grabbed my heart,” Hendricks said. “[But] I thought, ‘What can I do? I’m just a handbag designer.’” Eventually, though, she let her experience in fashion shape a grand concept: the Kwagala Project, an organization that raises funds for survivors of sex trafficking and other human-rights violations, in part through the creation of jewelry and accessories that the women make themselves. Since Hendricks founded Kwagala in 2008, the sale of these items has helped fund a vocational school, a college scholarship fund, and two rehabilitation centers, including one in Gulu called Total Impact House.

Total Impact House’s First Resident

By 2009, after a few years of prostitution in Gulu’s horrific ghettos, Joyce had nearly lost the desire to live. But then she met Pauline, a Kwagala Project director who offered Joyce the opportunity to be the first to move into Total Impact House. Joyce agreed, and there, she was given access to things she hadn’t had the comfort of enjoying in years, including regular meals and a safe place to sleep. She also took advantage of education and vocational training, eventually becoming the first to graduate from Kwagala’s vocational school.

Since then, hundreds of other young women have found hope for a better life through Kwagala Project. Though the women share common experiences, each story is different. “Most people think [it’s like] the movie Taken,” Hendricks said of the women and children they rescue. “But there are a zillion different scenarios. In the slums and Third World countries where people have zero resources, they’re [often] rescued from their own family members. We aren’t necessarily pounding down brothel doors, but we talk to them, educate them. We tell the family members that we’ll take care of their kids.”

How Chicago Has Stayed Part of the Story

Hendricks’s ties to Chicago have never stopped aiding in Kwagala Project’s mission. Local corporations such as Total Attorneys and MentorMob have funded rehabilitation centers and gotten involved through hands-on volunteer work. Individuals have also helped the organization thrive in creative ways: take Julie Hillery, PhD, a fashion-studies professor at Columbia College, who rallied her students to spread awareness of Kwagala Project through social media and marketing.

But any Chicagoan can get involved by buying the organization’s jewelry—100% of the proceeds go directly to Kwagala Project. The women also create packages of discounted fundraising bracelets, which purchasers resell to benefit both Kwagala Project and an organization of their choosing.

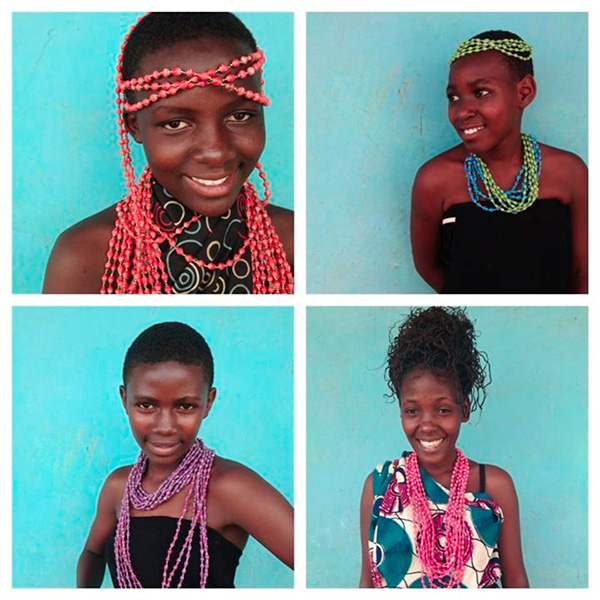

Jewelry Made from Recycled Materials

Although many find it hard to believe upon seeing the shiny, colorful beads used in Kwagala’s jewelry, they’re all made from recycled paper. Dyed paper is purchased locally (it’s a popular item at Ugandan markets) and cut into triangular strips. The women then roll the strips into beads, varnish and sun-dry them, and string them into bracelets and necklaces, which can range in price from $18.95 for a teal clasp bracelet to $26.95 for a short pink necklace.

It’s a technique that is remarkably similar to the mission of Kwagala Project itself. “[The bead-making process] represents who we are,” Hendricks said. “It’s a recycled material, one that once was considered garbage, but now is extraordinary jewelry.”

Photo: courtesy of Laura Ferkaluk

A Glimmer of Hope, Halfway Around the World

Nearly 8,000 miles away in Chicago, Kristen Hendricks was spending her free time ladeling out meals at local soup kitchens. Her day job was operating a private-label handbag and accessories company. But when she started learning about human trafficking in Africa, her life’s passion changed. She spent months researching it, then booked a trip to Uganda to see its reality firsthand.

“It grabbed my heart,” Hendricks said. “[But] I thought, ‘What can I do? I’m just a handbag designer.’” Eventually, though, she let her experience in fashion shape a grand concept: the Kwagala Project, an organization that raises funds for survivors of sex trafficking and other human-rights violations, in part through the creation of jewelry and accessories that the women make themselves. Since Hendricks founded Kwagala in 2008, the sale of these items has helped fund a vocational school, a college scholarship fund, and two rehabilitation centers, including one in Gulu called Total Impact House.

Total Impact House’s First Resident

By 2009, after a few years of prostitution in Gulu’s horrific ghettos, Joyce had nearly lost the desire to live. But then she met Pauline, a Kwagala Project director who offered Joyce the opportunity to be the first to move into Total Impact House. Joyce agreed, and there, she was given access to things she hadn’t had the comfort of enjoying in years, including regular meals and a safe place to sleep. She also took advantage of education and vocational training, eventually becoming the first to graduate from Kwagala’s vocational school.

Since then, hundreds of other young women have found hope for a better life through Kwagala Project. Though the women share common experiences, each story is different. “Most people think [it’s like] the movie Taken,” Hendricks said of the women and children they rescue. “But there are a zillion different scenarios. In the slums and Third World countries where people have zero resources, they’re [often] rescued from their own family members. We aren’t necessarily pounding down brothel doors, but we talk to them, educate them. We tell the family members that we’ll take care of their kids.”

How Chicago Has Stayed Part of the Story

Hendricks’s ties to Chicago have never stopped aiding in Kwagala Project’s mission. Local corporations such as Total Attorneys and MentorMob have funded rehabilitation centers and gotten involved through hands-on volunteer work. Individuals have also helped the organization thrive in creative ways: take Julie Hillery, PhD, a fashion-studies professor at Columbia College, who rallied her students to spread awareness of Kwagala Project through social media and marketing.

But any Chicagoan can get involved by buying the organization’s jewelry—100% of the proceeds go directly to Kwagala Project. The women also create packages of discounted fundraising bracelets, which purchasers resell to benefit both Kwagala Project and an organization of their choosing.

Jewelry Made from Recycled Materials

Although many find it hard to believe upon seeing the shiny, colorful beads used in Kwagala’s jewelry, they’re all made from recycled paper. Dyed paper is purchased locally (it’s a popular item at Ugandan markets) and cut into triangular strips. The women then roll the strips into beads, varnish and sun-dry them, and string them into bracelets and necklaces, which can range in price from $18.95 for a teal clasp bracelet to $26.95 for a short pink necklace.

It’s a technique that is remarkably similar to the mission of Kwagala Project itself. “[The bead-making process] represents who we are,” Hendricks said. “It’s a recycled material, one that once was considered garbage, but now is extraordinary jewelry.”

Photo: courtesy of Laura Ferkaluk BY: