Skin. It’s a beautiful thing. It releases pheromones, protects us from the elements, and has inspired countless artists with its radiant sensuality.

Turns out, it’s also covered in bugs. Human skin is pretty darn creepy, hiding mites and near-psychic abilities in its secretive layers. Read on for six spooky skin facts—just don't be surprised if yours erupts into swarms of goosebumps.

Insects live—and die—on your face.

By the time you reach adulthood, mites have taken up residence on your mug. Two intrepid species of slug-like arthropods—with legs!—snack on sebum and lay eggs while burrowed in your pores. A typical face boasts 1 brevis mite per sebaceous gland, and 3–6 folliculorum mites per follicle. They only crawl out at night to mate and, for all we know, laugh quietly while forming mustaches on your face. At least these face-pets don't defecate—not in the traditional sense, anyway. Instead, they excrete all the waste they’ve ever produced when they die. Which is maybe way worse.

Your skin hears things (and it might see, too).

We all know our brains transform speech sounds into meaningful content. Many of us also know that our brains rely on visual cues, such as unconscious lip-reading. Now, it seems even our skin gets in on the conversation by detecting the air fluctuations that accompany speech. When researchers emphasized "ba" and "da" sounds with faint, exhalatory puffs, they found that blindfolded test subjects heard "pa" and "ta" instead. Think that's amazing? Some blind people actually "see" through their skin, too, because of the way their brain's visual cortex rewires itself.

Some libraries have books bound in human skin.

It's not just a grisly rumor haunting social media. Some of the country's most prominent bookshelves contain cadaver-clad tomes, their authenticity confirmed by scientists. Perhaps the most infamous specimen is tucked into the shadowy archives of Harvard University's Houghton Library: Destinées de l'Ame (translation: On the Destiny of the Soul). Before its pebbled, tawny leather cloaked Arsène Houssaye's manuscript, it occupied the back of a human woman, reportedly a deceased patient from a psychiatric hospital.

Other examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy—the scientific term—live at Brown University's John Hay Library, which has three; the University of Georgia; the Mütter Museum; and the University of Pennsylvania, whose 19th-century med-school students made them by hand.

We live and breathe in a swirling cloud of death.

More precisely: dead skin. Roughly one billion tons of skin cells float through the air worldwide, living on as dust and thoroughly ruining every deep, yogic inhale you'll take from now on. One billion tons is a lot—roughly the weight of 133 million elephants—but it makes sense when you consider that we shed 50,000 dead cells every minute. (Our entire outer layer is replaced every two to four weeks.) Consider, too, that we're each toting around about 20 pounds of skin, and suddenly that teeming mass of expired tissue makes sense.

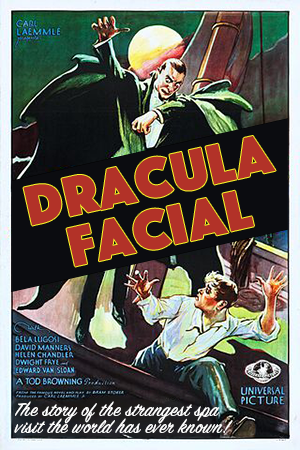

There's something called a vampire facial. And yeah, it's bloody.

There's something called a vampire facial. And yeah, it's bloody.

Though unconventional, the ghoulishly-titled treatment is pretty popular. Most notably immortalized in a selfie from a blood-slathered Kim Kardashian, the process involves a technician injecting the client's own platelet-rich plasma (PRP) into their face. And that's not even the eeriest thing modern-day sophisticates embrace in their pursuit of beauty—snail mucus, bee venom, lasers, and callus-eating fish (for pedicures) are all used in various skin-care treatments.

Some people have radiofrequency chips implanted in their skin.

It sounds like something from a neo-futuristic B movie, but it's true. The first human radiofrequency identification (RFID) chip was implanted in 1998. Its host, British scientist Kevin Warwick, used it to open doors and turn on lights for nine days before having it removed. Since then, increasingly high-tech RFID chips have been used, mostly by hobbyists with a deep, hands-on fascination with the technology. Some companies have developed chips for health and security applications, and an estimated 2,000 people wear them today.

Movie posters courtesy of Wikimedia Commons with modifications by Kelly MacDowell, Groupon.

Learn even more surprising facts about your face: