GROUPON GUIDE TO ANCHORAGE

How Deaf Servers Are Changing Diners' Expectations

BY: Mae Rice |May 21, 2015

BY:

Time to fill this bad boy with great products like gadgets, electronics, housewares, gifts and other great offerings from Groupon Goods.

Moe Alameddine makes you question things: whether deafness is as isolating as the hearing may think it is, for instance, or whether we should interview every restaurant owner about food. Talking to the restaurateur behind DeaFined makes questions about spices and butchers feel limiting.

That’s not to say that the menu doesn’t have a backstory that’s as interesting as the concept behind the Vancouver, BC, eatery. Moe was born in Lebanon, and DeaFined’s chefs prepare the Eastern Mediterranean food he grew up eating: hummus, fattoush salad drizzled with pomegranate-sumac dressing, watermelon and grilled halloumi cheese, succulent lamb flavored with imported Lebanese herbs.

But perhaps more immediately striking than the cuisine’s international connections is that Moe talked with me by phone—he’s one of the few staffers at DeaFined who can do that unassisted. Most of Moe’s team is deaf or hard of hearing, a deliberate choice designed in part to help alleviate that population’s chronic unemployment. And this isn’t a completely out-of-left-field move for him. Before opening DeaFined, Moe founded blind-dining restaurant Dark Table, where visually impaired waiters serve diners eating in pitch darkness.

I chatted with Moe about what he’s learned from his staff and his restaurants. (Don’t worry—we also covered the mechanics of how a deaf restaurant works. We had to ask.)

Moe’s waitstaff mostly communicates via American Sign Language, which most diners don’t know. It’s a language barrier that could bring most restaurants to a halt, but at DeaFined, it’s no big deal. When guests first walk in, they meet a bilingual host who acquaints them with the restaurant concept and ASL basics.

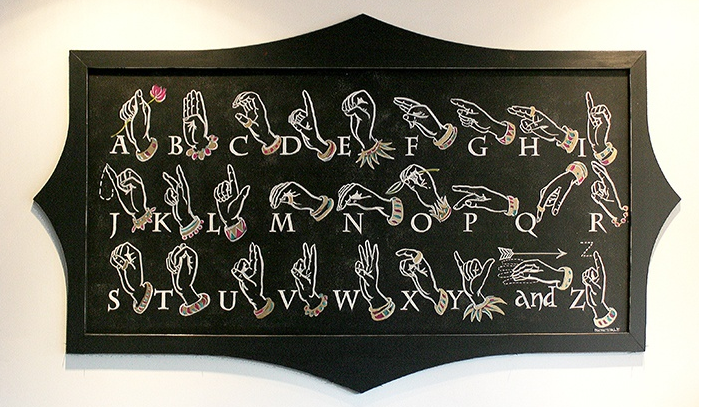

From there, diners have plenty of ways to flex their ASL chops during their meal. On each table, Moe and his team have left cheat sheets, with translations of key terms like “please” and “thank you.” Every menu item is accompanied by an ASL symbol, and an ASL alphabet hangs on one wall.

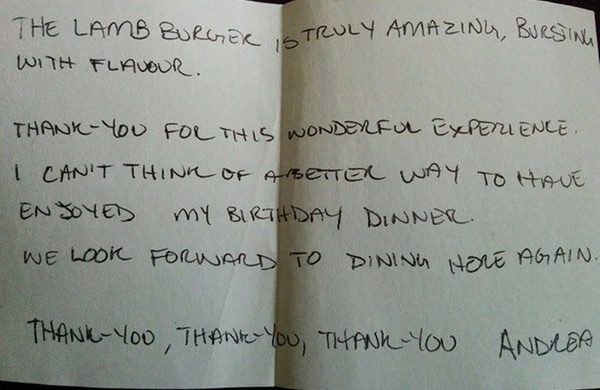

There’s a pad on each table, too, originally meant for diners who needed to explain complex requests and food allergies. However, diners also use them to write heartfelt thank-you notes to their servers. Before DeaFined had been open a week, Moe had amassed a museum-worthy collection of notes. "[The waiters] get papers from customers," he said. "'That potato was great!' 'My burger was excellent!' ... I have little notes now, in the office."

Here’s one love letter to good service and lamb burgers:

The key, he says, is simplifying the key restaurant processes. “People complicate things too much. I like to simplify things … make it realistic, you know?" Do that, he said, and a server who’s deaf or blind can do “a perfect job.”

Also, make sure they’re serving great food. Moe’s learned to take his time from his years spent helming restaurants. "You have to be very patient,” he said, and take your time with each plate. “The dish you're going to serve to the customer must be perfect. No mistakes are allowed." One dry lamb burger can lose you a regular.

Overall, it’s really not so hard, he said. He advises other restaurant owners to follow in his footsteps: "Think of hiring deaf people or blind people. … If I can do it, everyone can do it. A man landed on the moon, so how hard is it to train someone to take a dish from Point A to Point B?”

Photos courtesy of DeaFined